At a cursory glance, co-founders and husband and wife duo, Nadir and Yadira Thabatah, are an unusual pairing by most standards. Their dynamic defies societal expectations, considering Yadira is entirely blind and Nadir is legally blind.

They have often been told how inspirational they are as parents, members of society and founders of a nonprofit, all of which they’ve remarkably managed ‘despite being blind.’

Given their successful endeavours, admiration is certainly warranted. However, the compliments prefaced by “despite your disability” can be highly vexing. On a surface level, it’s seemingly innocent, and yet it can be offensive considering the buried assumption that disabled individuals are generally not expected to curate accomplishments. It’s that subliminal perception, mostly possessed inadvertently by society, that Nadir and Yadira are working to get rid of.

“When you are disabled and blind, people assume that you can’t. They insert whatever activity, thought or goal it is, then precede it with a “you can’t”. And that comes from the idea of what the abled body person thinks they would do in that situation. So to assume is very short-sighted,” said Yadira.

This perception leaves room for a double standard, especially when parenting is involved.

While everyone has their motivation for adhering to the pandemic’s regulations, there’s an additional layer of risk for parents who are disabled, said Nadir.

“When something happens to a child that has no parents with disabilities, people say, ‘oh, it happens’. But when you’re a blind parent, and something happens to your kids, that’s not the case. It’s because “you’re blind and you shouldn’t be a parent’,” he said.

As a family, they’ve had to pay the repercussions of societal projections.

Husband and Wife Yadira and Nadir pose for a photo.

Perhaps the happiest of days in a parent’s life is the day their child is brought into this world - that was certainly the case for Nadir and Yadira. And yet, that joy was interrupted and quickly replaced with horror and panic.

Their eldest child, Abdallah, was born perfectly healthy but remained in the hospital for a week upon his arrival after a nurse assessed that the couple were unfit to be parents due to their disability. “Who is going to help you take care of your kid?” was the nurse’s biggest question and concern.

The new parents threatened lawsuits and called on their community to advocate on their behalf.

But their situation is far from unique. Discrimination against Blind parents has become a prevalent enough issue that legislation has been introduced. In 2018, some U.S states including Ohio and Nevada have passed bills preventing government agencies from having children removed from Blind parents and denying Blind foster parents consideration for adoption on the basis of their disability.

It’s further proof of the disabled community lacking basic rights.

“Being a Blind parent is actually not the difficult part, the difficult part is having to deal with society who is deciding for you what box you should be in. They tell you what you can and cannot do because it makes them uncomfortable otherwise,” said Yadira.

Even the prospect of marriage or children for a Blind or disabled individual is considered outlandish. It’s seldom heard of because they’re viewed more as “furniture'' or a “blip” on society, and so there’s no expectation to be married, said Nadir.

Their personal journeys encouraged them to start a nonprofit together, Islam by Touch, the first North-American Muslim organization working to provide English-Braille Qurans and Islamic resources to the Blind community.

“There’s been braille Qurans for decades. But we’re the first to take an English translation that scholars recommend and put it into braille. And not only to put it into braille but also to properly format it. Some things don’t fit or translate easily into braille, like footnotes,” said Nadir.

For Yadira, who is a revert to Islam, the lack of accessible Islamic literature and Da’wah material was alarming to her and served as one of her motivations to start Islam by Touch. Filling that void has propelled the nonprofit to the forefront of efforts intended to facilitate the integration of Blind individuals into the Muslim community.

Aside from producing the Braille material, they ensure quality is accounted for, a measure that can be neglected during the production of Arab produced Braille Qurans overseas. Arabic Braille Quran readers have told Nadir that their copies are riddled with mistakes.

“We take pride that we have proofread the entire master copy. It’s strenuous and a lot of work but if you want quality and you want to maintain the accuracy and make sure that information is being given in a proper manner. Especially when you get a non-Muslim asking for the Braille Quran so they can read and learn. Then we’ve also had Muslims who are so happy that this exists,” he said.

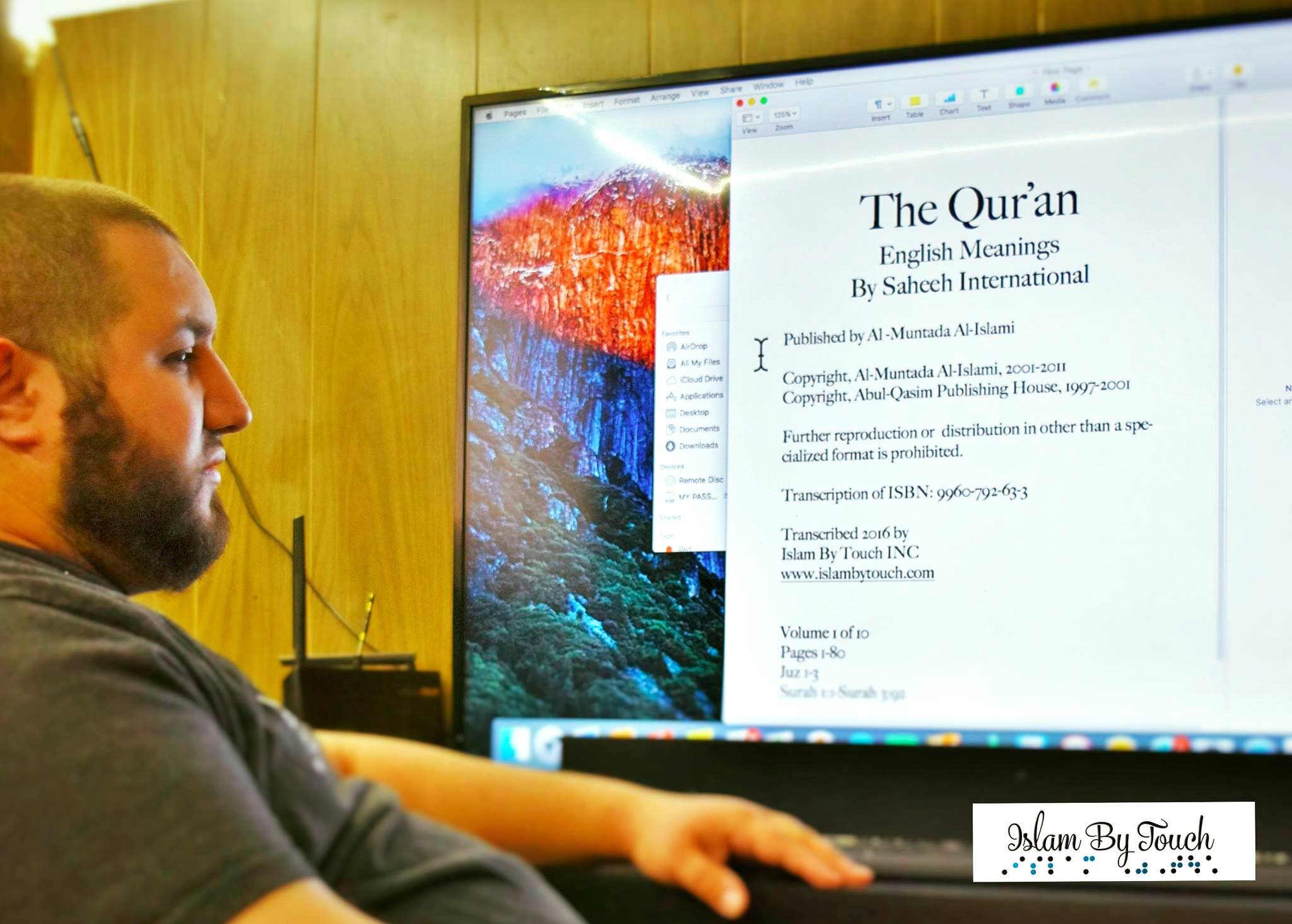

Nadir at a computer screen opening up a translation program to begin printing of Volume 2 of the complete set of the Quran.

Islam By Touch at the Islamic Society of North America convention.

While one aspect of the organization focuses on providing accessible material to the Blind community, another focus is on educating the sighted community on how to appropriately interact and treat Blind and disabled people.

The education facet often takes the form of Khutbas or “Family Night” workshops at mosques. It can often be a source of bafflement and mild agitation for Nadir because it exposes how misunderstood and underestimated the Blind community is by society.

“But what if something had happened to you? Like a car you didn’t see coming?”

Nadir stares at the community member who posed the question, taking a deep breath in order to maintain his chill before delivering his response.

“You don’t have to physically interact with them in order to help them,” he counters. “We’re not talking about extreme circumstances where a car might hit me. All you have to do is ask a simple: ‘do you need help?’.”

Often in these workshops, Nadir asks participants to reenact what they would do upon seeing a Blind person with a walking stick waiting to cross the street. He has presented this scenario to diverse congregations across masjids in America and without fail, there’s always someone who admits to grabbing the Blind person by the arm and forcing them across the street.

Being visually impaired himself, he has heard and experienced this response ad nauseum.

“I’m from Jersey, you grab me like that and we’re going to fight,” Nadir jokes with the crowd.

He realizes their good intentions, however, he holds the belief that good intentions are meaningless if the outcome serves to offend.

“Ask first before you act because the last thing you want to do is offend,” he advises. “If you want to gain Allah’s favour, the last thing you want to do is offend a brother or sister. So much can be shrouded in good intentions but if you offended me then what good is your intention?”

Wrestling with the Muslim community’s perception of Blindness has been a real challenge. Often, disability is perceived as a curse or as an opportunity for charity. Those perceptions are what initially deter Blind and disabled individuals from coming out in public and when they don’t show up, no one bothers to supply resources for them, said Yadira.

Nadir in Denver, Colorado before an event at a mosque.

“Imams will often say they don’t know any Blind Muslims in their area,” she said. “People say they don’t know blind people, but we’ve deduced that they’re there, but you have nothing for them.

Additionally, there’s an extreme lack of education in the Muslim community regarding the Blind community. For Yadira, who uses a guide dog when going out, she has had numerous encounters with disgruntled Muslim Uber drivers.

“I have lost count over how many times over the years I have been refused a ride or how many times I’ve had to report a driver. The problem has been so pervasive that Uber has put in a specific ruling, where on the app, there is a specific prompt that says, ‘are you having service animal issues?’,” she said.

The normalisation of guide dogs is hugely important to the Blind community because it offers them a means of independence - which is generally a foreign concept to many sighted, and even Blind people, said Nadir.

“This is very big within our community. There’s this disconnect between what reality is and what people think it should be. I’ve met so many blind people, Muslim and non-Muslim, that are absolutely helpless,” he said. “They can’t do anything for themselves. Why? Because their families and their parents and surroundings and the environment have not been conducive for them to be independent.”

In many cultures, Blind people are treated differently, according to Nadir. It’s extremely rare for a Blind woman to be married. While Blind men are encouraged to, so that someone may take care of them. Urging and educating the Blind community on how to live more independently is an initiative Islam by Touch hopes to one day launch.

“We would love to send someone to a Blind person’s household and teach them orientation and mobility, like how to use a cane. Or to teach them something known as independent living, like how to clean up your environment or how to cook things, or iron and all of these things. We would love to do that, but you need to hire employees. You need people that have degrees in these themes,” said Nadir.

As imperative as the education on the disabled front is, the implementation is costly, and the current cost of operation is already high.

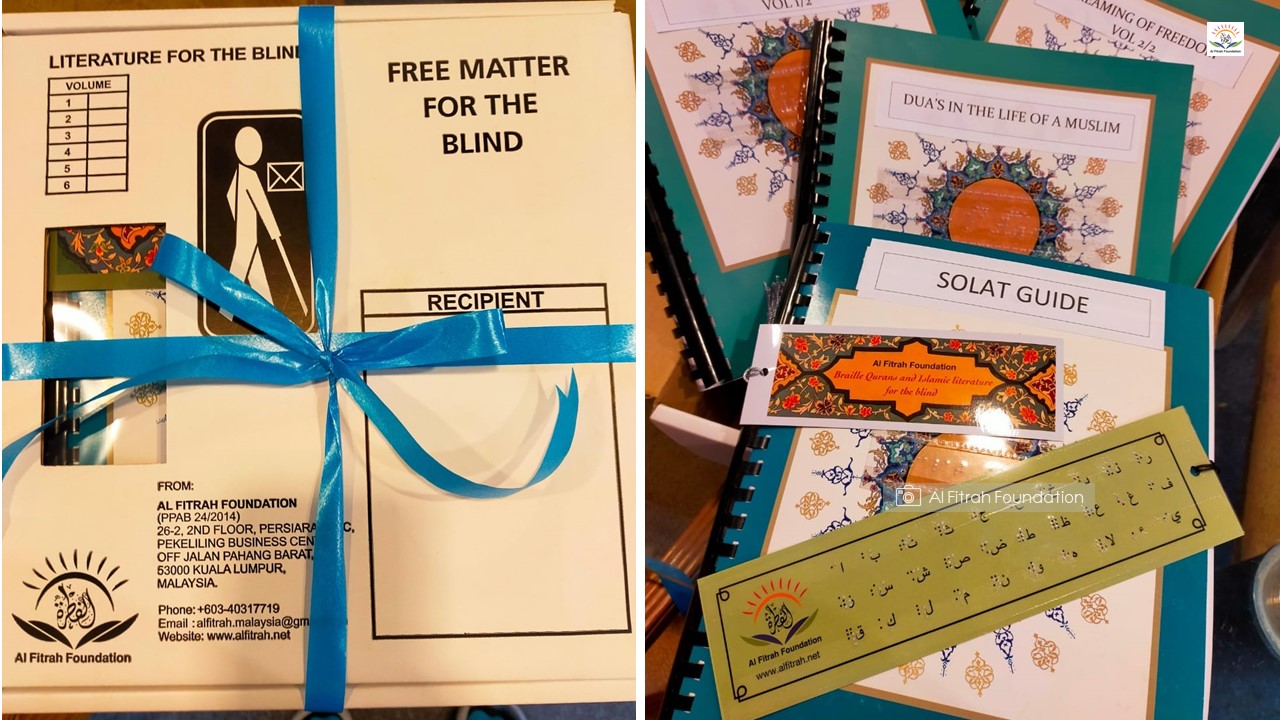

An HP colour printer might cost anywhere between $100-200, but a non-mass production Braille embosser printer cost $5,000. The hidden costs of production fall everywhere, from the type of paper to the sheer amount of volumes it takes to produce one full Quran.

“It’s stupid expensive. Just for a pack of braille paper, it cost $50 for 1,000 sheets of paper,” said Nadir. For perspective, the same price could purchase 5,000 for regular printed paper.

“A 50 pack of covers, to cover 25 books, is $100. It takes 10 volumes to make up one Quran. There are 20 covers right there,” he said. “ I then take those boxes, 3-4 boxes, at a time to the post office and ship them out.”

The total cost of one copy, including production, maintenance, and distribution is $250. And yet, despite the pricey process, Islam by Touch provides Braille Qurans free of charge.

“The blind community is a very poor community. 75% of the blind community and the visually impaired, live at or below the poverty level,” said Nadir. “Even within that accessibility space, everything is expensive. Almost every accessible tool we have is extremely expensive.”

Lack of funding is one of the organization's greatest issues, and after COVID-19 ravaged the world, Nadir and Yadira took themselves off of the payroll. Their organization for the nonce will continue to produce and ship out Braille Qurans, however, the duo remains optimistic and insatiable.

“Alhamdulillah, I’m so happy with what we have achieved in such a short amount of time. When it comes to Blind and Muslim, we are the first name that comes up. Within four years of doing this by ourselves, I think that’s an amazing achievement,” said Nadir. “Over 450 braille Quran’s being shipped around the world is awesome. But we have so much more we could be doing.”